History of coffee

Every morning shortly after sunrise, Sa’id Ahmad walks through the winding alleyways of the old city of Sana’a to open up his little shop. When he gets there, he puts water on an old kerosene stove to boil, arranges small glasses on the counter, and waits for the local men to come to his shop after morning prayers at the mosque. What brings them to him is the specialty of house: Yemeni coffee.

Nobody knows when someone in the ancient capital of this barren land at the south-western tip the Arabian peninsula first hit upon the idea of roasting the fruit of the coffee tree on flat stones in the sun and then grinding them up and boiling them in water. All we know for sure is that when the first European seafarers reached the port of Al-Mukha in the 16th century, the Yemenis had already developed a taste for a drink that was to become a major feature of world culture in the space of just a few decades. The coffee that Portuguese and Dutch sailors brought back from the place they called “mokka” on their travels round the Horn of Africa is know by the Yemenis as “bunn”. In the history of their country, this word is linked to a brief economic golden age. When shopkeepers like Sa’id began opening their own little shops in one European trading city after the next, Yemen still had the monopoly on coffee.

Yemeni beans are still sought-after today, and are a rarity on the world market. After oil, coffee is the second-biggest traded commodity in the world, and 25 million people around the globe earn their living from it. However, ever since a Muslim pilgrim brought the seeds of the plant (officially knows as Coffea Arabica since 1737) to southern India, where it was discovered by Dutch traders and taken to Java, Yemen has hardly benefited from this circumstance at all. Today, coffee is grown on a massive scale in Indonesia and Central and Latin America.

The plant is believed to have originated in the highland forests of Ethiopia in the districts of Gamo-Gofa, Sidarno and Kefa (also known as Kaffa). This latter name sounds rather like the Arabic word for coffee, Qahwah, from which our own word for the drink is derived. However, language experts do not have any firm proof of this interpretation. We do at least know that the Arabic word for coffee is related to a rule of conduct applying to Muslims. “Qahwah” is the wine that followers of the Koran are forbidden to drink.

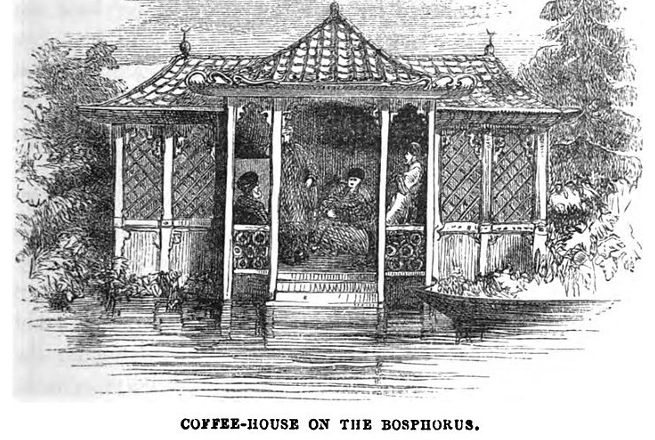

Early European coffee culture is very well documented. It began after the Thirty Years’ War in the mid-17th century, when the first transport routes were opened up from the Arabian peninsula across the sea to Italy and overland through the Balkans. At the same time, trading cities were developing their sales networks. Although coffee houses roasted their coffee beans themselves, pharmacists and travelling Turkish salesmen sold the beans unprocessed to private households.

The main thing that coffee seemed to bring out in people was a penchant for socializing. In the mid-17th century, it was considered fashionable in Europe’s royal courts to consume coffee in rooms decorated in Oriental style while wearing Turkish clothing. This trend was called “mode à la turque”. Like all fashions, it soon passed, as did the concerns of the Vatican, where Pope Clement VIII, fearing the hidden dangers of a possibly devilish drink, cautiously baptized his first cup before succumbing to its wonderful aroma.

Today, nobody believes that coffee is an aphrodisiac anymore. This is partly because the upcoming middle classes, many of them of Protestant faith and with a rational view on life, took a more objective approach to coffee drinking. At first, coffee beans were believed to be a substitute for the widespread alcoholism of the day. Later, having an early morning cup of coffee became a symbol of bourgeois industriousness and sobriety, coupled with a desire for good company and lifestyle. Coffee was drunk in various different places –in public coffee houses, the exclusive domain of men, or in private, largely female environments known as “coffee circles”

Coffee mobilizes energy reserves

Coffee drinking seemed to be the ideal symbol for a new social class that liked to take the old customs of the nobility and brew them up into new, more down-to-earth fashions. The love of all things decorative remained, as was expressed in the hand painted porcelain coffee sets for which people paid large amounts of money.

Coffee became popular among the working classes in the 19th century, initially as a means of supplementing a meager diet. A sip of coffee –even if it came from a cheap tin or enamel pot at a street vendor’s stall –was in some way a substitute for a hot meal. People drank coffee in short breaks during long working days to help them mobilize their remaining energy reserves.

The increasing popularity of coffee and the ever-expanding growing areas in which it was produced stimulated the creativity of the roasting establishments and coffee houses. In Italy it was so well received that the Italian language developed a broad vocabulary for its legendary variations: cappuccino, macchiato, latte macchiato, ristretto, lungo, corretto, caffè latte…

And now, a little source of inspiration:

Viennese Coffee

Ingredients (2 servings)

100 gr semisweet chocolate

500 ml espresso coffee

200 ml whipping cream

Sugar to taste

1 pinch of cinnamon

- To prepare Viennese coffee, the first thing you have to do is make the espresso. This method is faster and as a result the coffee is more concentrated.

- Pour the hot espresso into two individual cups. Add a teaspoonful of sugar and stir. In a saucepan, melt the chocolate with 50 ml of the whipping cream, preferably in a bain-marie, and stir.

- Next, pour the mixture into the two cups of coffee and stir. If you wish, you can mix the coffee with the chocolate before serving it and beat it for a smoother texture.

This entry has 0 Comments