Ouef au miroir

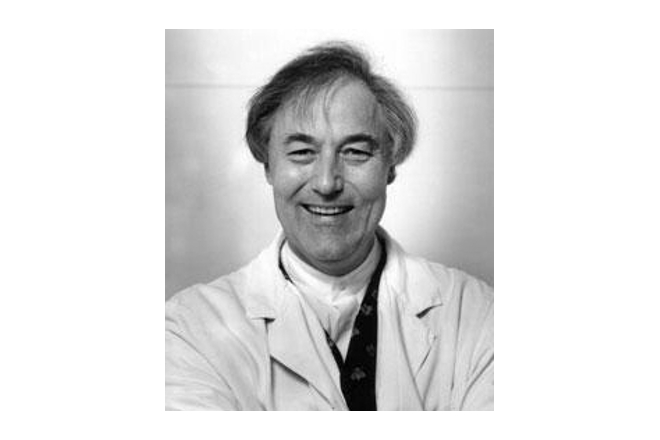

Molecular gastronomer Hervé This-Benkhard has been fascinated by chemistry ever since he was a child, and has written several books on cookery and its scientific principles. He is also scientific adviser to the magazine „Pour la Science“ and Director of the Chemical Laboratory of Molecular Gastronomy at the famous Collège de France in Paris.

There are a lot of old rules in cookery: it is said that berries should not be stored in a galvanized container, that green beans must be cooked in salted water in a pot without a lid, and that a teaspoon in the neck of an opened bottle of champagne will stop the fizz from escaping.

Hervé This-Benckhard was intrigued by these cooking tips, and started experimenting to find out about their scientific basis. The fried egg was not overlooked. It is one of the easiest dishes to prepare, the one that enables us to feel self-sufficient at an early age. And after all the fried eggs made in a lifetime, any gourmet is bound to want to excel and find perfection in the fried egg.

This happened to Hervé This-Benckhard, following the guidelines set in La Bonne Cuisine by Madame Saint-Ange: “The egg yolk is still runny, although thickened, enveloped in a delicate white veil that makes it shimmer or shine,” hence also the old French name, “oeuf au miroir.”

Hervé This-Benckhard shares his excellence, enabling us to achieve this outcome:

In a flameproof pan, whose diameter should be no more than twice as large as that of an egg, melt a walnut-sized piece of clarified butter.

The diameter of the pan should be no more than 15 centimeters, so that no “shelf” forms with a thick layer around the edges. This would not be good, since the thinner section would be cooked through before the thicker section had time to solidify.

How to make clarified butter: melt the required quantity of butter in a small pan for a good 10 minutes over a very low flame. At the base of the liquid, a cloudy layer forms. This is the clotted casein. The upper, clear layer is made up of purified fat. Now carefully decant this upper layer from the base liquid. Allow it to cool, and that’s all there is to it. It melts, but it doesn’t sizzle and it doesn’t burn. In fact, you can even heat it to 190º without its decomposing–in other words, you can also use it for frying. Dishes fried in clarified butter have a much finer flavor than dishes fried in oil.

Allow the melted butter to cool down again. Then, break one egg into each frying pan. Only salt the egg white around the yolk. Sprinkle evenly with white pepper.

But why shouldn’t you salt the yolk? Because it would spoil its appearance with little dark pock-marks. The salt “cooks” the yolk by absorbing water from the areas it comes into contact with, causing the yolk protein to coagulate.

So if you only salt the egg white protein, which takes longer to cook, you balance out the two different solidification temperatures and end up with an evenly-cooked egg.

Allow the salted egg to rest for a minute and then cook it in the oven set at a very low temperature. It’s ready when the egg white has turned milky-white.

By cooking it in the oven, the egg keeps a uniform consistency, but still remains creamy.

Not as simple as it seems: the perfect fried egg is a true art.

This entry has 0 Comments